Bøker

Tilgjengelige publikasjoner av Bodvar Schjelderup

Kildespeilet

Se det usynlige

Utstillinger

Tidligere og tilgjengelige utstillinger

akhnaten’s friend and mentor

akhnaten – rise and fall

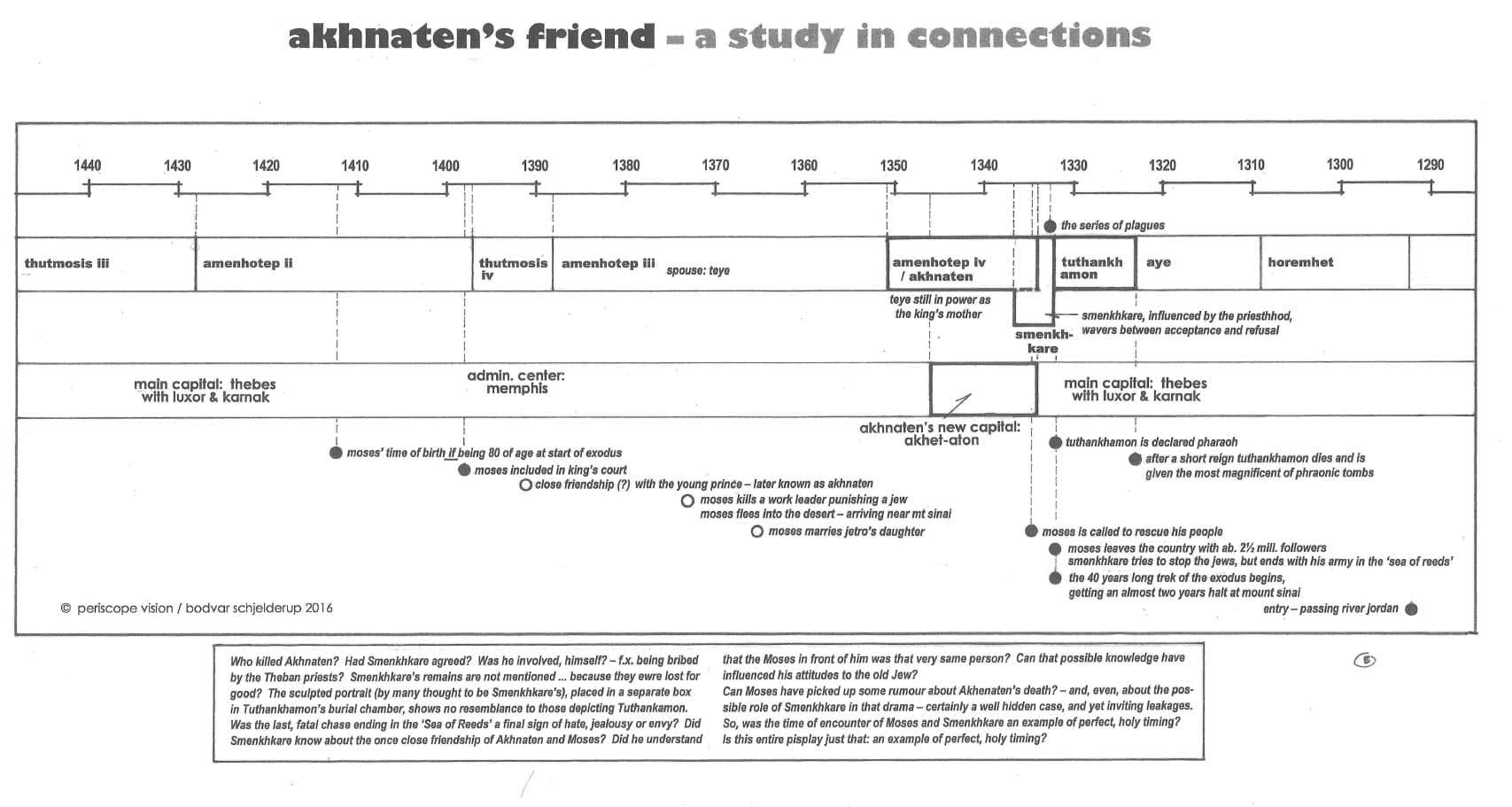

The theme was presented me with full weight some eight or nine years ago by one of the most ambitious books from Verlag Könemann – on ‘Egypt and the Pharaonic World’. Studying the list of pharaos I got aware that some minor uncertainty was still prevailing concerning ates, even concerning the 18th dynasty. The numbers given caught y interest, though, and a sequence of questions and ideas surfaced.

Myself I’m an architect, researcher and author – but neither archaeologist nor egyptiologist. My special studies concerning the Great Pyramid started in 1977, step by step leading to some documentations and, in 2004, to a quite extensive twin-exhibition in the Bibliotheca Alexandrina: ‘The House of Memory’ (symbols & codes) nd ‘Unfolding the World’ (Mercator map discoveries).

My presentation may have seemed too controversial, both concerning ideas, comments and a few non-Egyptian themes. I admit I haven’t ollowed well trodden tracks, yet my discoveries into ‘sacred geometry’, as well as architectural, geographic and religious topics have been of some value … not least by indicating that phenomena that are mostly considered separate, do prove striking interconnections.

What first and foremost caught my interest was the life and fate of Amenhotep IV – the pharaoh who openly crossed the traditional, priestly views and doctrines, announced a monotheistic program, started the building of a new capital city, and changed his name to

Akhnaten. His ideals also were expressed in diverse other ways, and his attitudes against traditional Egyptian orthodoxy were clear.

The localization of the new capital, Akhet-Aton, seems an act in order to express a stronger connection between Upper and Lower Egypt – and, most likely, even to get Thebes as well as the Delta centres at arm’s length. The orthodox men in power clearly felt their positions

threatened, and this fact would quite naturally nourish potential plans of uproar. Even many of his own officers may have hated him.

A central theme here is his announcement of the One God. Even his father, Amenhotep III, had presented himself as representative of the Sun, also starting to erect a capital of his own south of Memphis. hat seemed so amazing to me was this immensely radical change,

and I wondered what could have contributed to it. A deep-going religious vision seemed the only key to understand the phenomenon.

Akhnaten may have been a visionary, sensitive and gifted ruler – although he must have misjudged the (more or less obvious) consequences. When he was forced to surrender his despair naturally was bottomless. But such a fate was a rather common experience to men

of power challenging their context, including f.x. the Danish Harold Bluetooth and the Norse Olav Haraldsson.

The two Nordic pioneers were among the very first Christian kings. Their policy came to be a threat to ruling conventions, causing also their death. At Akhet-Aton we may imagine a hate of yet greater dimensions, causing Akhnaton’s brutal death – or disappearance. No

trace of him seemed to inform about his fate … until recently, when new finds in the Valley of Kings have decovered a possible hit.

Whatever can be definitely proven concerning the end of his life, theenigma of the radical king has survived him, giving Egyptian history a just as radical new headline. After sixteen or seventeen years of rule he was virually razed out of his time, and many sculptures, reliefs and inscriptions praising his magnificence were destroyed. His mother Tiye and his daughter Meritaten were possibly murdered.

chronology as key

Ine the great Könemann volume a chronology according to Jürgen on Beckerath, Akhnaten’s reign lasted from -1351 to -1334. What seems alarming is that the succeeding pharaoh, Semenkhkare, may have been his co-regent during the last period, about two or three years before the uproar. Akhnaten had had to accept another at his ide – possibly a son or nephew(?), but, in any case not a friend.

After Akhnaten’s fall Semenkhare demonstrated the traditional polytheistic theologies, and most likely his connection with Thebes was intimate enough. Whether he agreed positively in the getting rid of Akhnaten, or – just as possibly – was paid by orthodoxy to make it

happen, we may not know. But the scheme is clear. His role as sole ruler seems to reveal egotistic and violent attitudes.

The next question concerns Semenkhkare’s short reign. He disappears from the list of pharaohs less than two years after Akhnaten’s fall. This fact invites a new set of questions. Also because the election of the succeeding pharaoh, the very young Tuthankhamon (a yet

younger son of Akhnaten) may seem an act of haste and despair. So, the questions concerning Semenkhkare seemed most important.

And still we don’t know much about him. Also his name and glory seems to vapourize. Rumour says tha a box containing his remains were found in Tuthankhamon’s tomb. In any case, the connected sculpted portrait didn’t resemble those of Tuthankhamon. Was thisSemenkhkare? Or should it (and the possible included human remains) represent him because his own, true remains were absent?

Even what has seemed to be Akhnaten’s remains is lacking the usual pharaonic signs of celebrity. Were both he and his successor hated, in spite of all difference? Or is the ignorance concerning Semenkhkare to be interpreted otherwise? Had things happened that had turned popularity into aversion? What can we possibly know, or, at least, guess with some probability?

The contrast to the celebrations of Tuthankhamon seems to support this latter idea. There had been a need, not only to hurry the election of a new pharaoh, but, also, to stress this new king’s special import-ance. Perhaps not because he deserved it, but because the situation demanded such an exceptional change. Having quit Egypt of rulers of dishonour would amplify the need to glorify the successor.

Something had happened … Can chronology give us a hint? Should we know of events which for some reason are forgotten or ignored or – even – just as unwished as informative guides? One certain event may fit in – and with great precision. It is not entirely Egyptian, how-ever. It announces a possible controversy with Semenkhkare which Egyptian sources are entirely mute about.

The alternative source is the Hebrew bible, the Torah. Whose first book, Genesis, concludes by telling about Joseph, sold as a young slave to an Egyptian officer of the crown and ending as Minister of State, in dignity next to the pharaoh. Then, in the second book, Exodus, a person named Moses appears. He comes to dominate the scene there-after, continuing to do so in the next books.

According to chronicle Moses most likely was born during the rule of Amenhotep II, more than twenty years before Akhnaten’s father, Amenhotep III entered the throne. The conditions of the Hebrews still living in Egypt had become harsh; wealthy and poor alike were treated as slaves. The men were sent to work in gold-mines and other places of hard work. And all firstborne sons were to be killed.

moses

The source is Hebrew. Totally. To that extent that no single Egyptian perspective of life, cultural state or religious ways are mentioned. This phenomenon is significant in many religious contexts: no interest or mention of foreign values was allowed to pollute the air of faith and religious practice. The Egyptian attitudes were almost just as rigid. But Semenkhkare was to add a moment of his own …

The Torah says that Moses’ mother couldn’t bear that her newborn baby should be killed. In her desperation she pitched a basked, thus having made it a watertight vessel, put her swaddled son in it and launched it onto the river Nile at the time when pharaoh’s daughter used to arrive for her daily bath. Moses’ elder sister, Miryam, was watching, hidden in the reeds. And Moses was seen – and rescued.

Miryam emerged, asking to help and promising to find a nurse. The princess was pleased to get a reasonable solution, but demanded that the boy was to be dedicated to the Palace when he was grown. The next mention of Moses is a something happening during his member-ship of the court. He is agitated seeing an Egyptian officer punishing a Hebrew slave and kills the officer in anger.

Moses’ had to flee, abandoning all goodwill and wealth. After a rigorous escape we find him in the desert of Midian, near what came to be the ‘Mount of God’. On the Sinai peninsula. There he was accepted as shepherd, and for many years to come he endured a life in poverty. But one day he helped the local priest’s daughter to water her sheep. He was invited to her home, and eventually married her.

Moses had lost much. As the time went by the dreams of his youth had faded into grey shades, and future offered no promises. But one day something very spectacular happened. He got aware of a bush in flames, but the flames didn’t swallow it. He went closer – and a voice told him to halt and take his shoes off: the ground was holy … He was given a message, a calling which he in no ways felt prepared for.

The Voice announced itself as the God of Israel and asked him to re-turn to Egypt. He should gather the Hebrews, tell them the time of departure was near, and ask the pharaoh for a collective permission to leave the country. The Voice told him there would be no danger; his past was forgotten … But Moses was shocked. This was indeed a miracle. But he excused himself; he wasn’t able to folow the calling.

The Voice told him to connect his brother Aaron; the two together would manage. And his enterprise would give success. At last Moses accepted. The next times he’s mentioned, are in dialogues with the pharaoh. The king wavers between refusal and permission. After each refusal a judgement hits the Nile Valley: plagues, myriads of insects, the Nile red with blood. Then a final permission is given.

Four and a half century after Joseph was appointed Minister of State the Hebrews gathered near the west bank of the watery ditch where the Suez canal is located today. Then they realize the pharaoh is arriving with a host of soldiers, horses and carriages. He’s going to stop them. Then a most strange thing happens: the waters in the ‘sea of reeds’ divide, and they pass across to the east bank.

The king and his troops are in the middle of the ditch when the waters return, says the story. All get drowned; the king’s last attempt to break down the Hebrew emigration ended in total loss and death. Thus, a wonder had saved the fleeing Israelites. An alien dimension had – once again – entered the scenario. The famous Exodus had got a dramatic start. And the drama was to continue …

blinking pictures in the dark

Back to the young prince. He was shocked. Nonetheless he may have hoped his vanished friend would escape his persecutors. Love and mutual attitudes are not easily razed out. His father, Amenhotep III, had accepted the boy’s warm sympathy towards the Hebrew stepson. This attitude was abruptly exchanged by disappointment and anger. So, why should this happen? Could it be repaired?

The loss was unbearable. His walks with this elder friend had been so enlightening. A brand new vision of purpose and meaning was sown in the boy’s mind. This is, I think, the only way to understand the radical program developing in his brain. Step by step the prince saw that he had to act on his own, to unfold his ripening vision and, by so doing, fight the troubled memories.

Moses himself knew he had spoiled any chance to give the boy a mature concept of vision. In his self-inflicted exile, sheep and goats, wife and children had become his lasting home. Uncertain as to Akhnaten’s attitude to him after the disaster, all hopes of a restored relationship were gone. He was gnawed by sorrow, knowing he had betrayed the boy as well as the unfolding vision … his true mission.

The exiled Moses was most likely quite unaware of the immense wave of radical change his role as mentor had caused. He hardly was aware that the new pharaoh had begun to unfold his overconfident program, where he challenged competing authorities and overthrew enemies, eager to realize a paradise by which he was to vitalize his country and people, from top to bottom.

As to Moses, the encounter with Semenkhkare was the very first. The pharaoh would hardly guess this aged Hebrew had been his father’s childhood friend. And Moses had no need of any mention concerning the past. He also understood he’d have to avoid any mention of Akhnaten’s disappearance. To Moses the encounters with the pharaoh likely were a subtle balance between risk and hope.

So, Semenkhkare didn’t identify Moses. Maybe Akhnaten had menti-oned those important childhood memories. But after Moses’ flight this was a theme to renounce. The old man in front of him was defi-nitely no anonymous anyone. He was worth listening to, but not one to be dribled by. His stubbornly insisting demand concerning the entire Hebrew colony was not to be met without solid friction.

Semenkhkare was most likely a person in restless wavering between options, afraid to withstand the men of religious power. He even may have opposed and betrayed Akhnaten’s program. Even caused his death, although indirectly. Now, concerning the Hebrews, he both detested and depended on those trouble-making bastards. But, suddenly, after repeated refusals, the gate to emigration was opened.

All became a disaster, though. The fatal loss in the ‘sea of reeds’ made Semenkhkare’s religious allies panick. Such a fool of a king! Such a disastrous misuse of men, horses and materiel! How produce a painless repair? How neutralize rumour and explain away those horrible facts? How restore the sense of pharaonic divinity? The moment may have been one of the darkest in Egypt’s history.

The next step seemed obvious. The young Tuthankhamon was ready to step in, supported by an amplified wave of cult and glamour. Did he feel joy, or fear? Was he tempted by homage and promises, or, can threats or bribe have played a role? From the very first moment he was the very object of a forced grandeur. But what did the young king think and feel? Were his nights without nightmares …?

We don’t know the answer. But he may have known too much to make him at ease. Awkward emotions and observations may have been co-working agents leading him to an early death. His supporters had hoped he would subdue the catastrophe. Instead they filled his tomb with an unsurpassed avalanche of riches. Resignation was not to have the last word. But afterwaves always go on swelling.

+++

The last word may still be in waiting. The KV63 excavation can have led to conclusions I haven’t heard of. But I do suspect that (one of) its secrets may be named ‘Semenkhkare’. A chamber smaller than many others of the kind. Having had no function as burial room, made ready but, for some reason, getting a different function – even from the very start. Semenkhkare was invited – but didn’t appear …?

It’s more than possible he ended his life in water. I’ve heard of no documentation, however, from Ferdinand de Lesseps’ Suez Canal project mentioning remains of carriages, wheels, weapens, skeletons … The digging machines may have been too unsensitive, of course. Watching eyes may have focused on quantities, not on qualities. And more than three millennia may have made oblivion coagulate.

landing

These few pictures are developed in the darkroom of imagination. Not supported by professional knowledge, but, rather, floating on a surface of visions as to how things may have happened, may have been linked together, may be interpreted. Without any professional authority I declare that I see no alternative scenario, more able to draw a trustworthy picture.

I do hope for comments. I came too late to present the ideas to Dr Otto Schaden, the inspiring leader of the KV63 excavation. I could have presented myself years ago, but fully aware of my empty voids of knowledge and correspondingly afraid of making a fool of myself I all the time postponed an open announcement. But television docu-mentaries gave me another solid name: Dr Salima Ikram.

I’m convinced we – as humanity(?) – have entered a state of con-ception where the walls separating given zones of view and practice, ratio and faith, are mouldering. Thus I think – or, at least, hope – that this encounter of the two mentioned sources may have a chance to make a life together and, perhaps even, to raise children. What if KV63 chooses to be a gate to that possibility?

Trondheim, Norway, March 28, 2016 Bodvar Schjelderup

Semenkhkare(?) and Moses, as recorded in the book of Exodus:

(Chapter : verses. The text follows, in principle, the King James Bible version.) 5:2 (To Moses and Aaron:) «Who is Yahweh, that I should obey his voice to let Israel go? I do not know Yahweh, neither will I let Israel go … … » 5:8+ (To Pharaoh’s officers:) «They (Israel) are idle! … Let more work be laid upon the men, that they may labour harder, and let them not regard hard words!» 7:17+ (Moses to Pharaoh:) «Thus says Yahweh, and by this you shall know that I am Yahweh: I will smite with the rod in my hand upon the waters in the river, and they shall be turned to blood. And the fish in the river shall die; the river shall stink and the Egyptians shall loath to drink of the water …» 8:6+ (This happened, and after seven days Aaron, according to Yahweh’s order,) «stretched out his hands over the waters of Egypt, and frogs came up and covered the land of Egypt …» (but) the Pharaoh «didn’t listen to them.» 9:21+ (According to Yahweh’s order) «Moses stretched his rod towards heaven, and Yahweh sent thunder and hail … and fire mingled with the hail; there had been nothing like it in Egypt since it became a nation … «And Pharaoh called for Moses and Aaron and said, «I have sinned this time; Yahweh is righteous, and I and my people are wicked. Ask Yahweh to send no more thunderings and hail, and I will let you go; you shall stay no longer.» … «and the thunders and hail ceased.» (Seeing this, Pharaoh) «hardened his heart, and he refused to let the children of Israel go.» 10:3+ (Moses and Aaron to Pharaoh:) «Thus says the God of the Hebrews: How long will you refuse to humble yourself before me? If you refuse to let my people go, I will bring locusts that cover the earth, so that no one will be able to see the earth. And they (the locusts) shall eat what still is spared in the fields and fill the houses …» 10:16+ (Pharaoh to Moses and Aaron:) «I have sinned agaist Yahweh your God, and against you. Therefore I pray you: forgive my sin only this time …» (The locusts dis-appeared, but Pharaoh) «did not let the children of Israel go.» 14:9+ «… The Egyptians pursued them, and the horses and chariots, his horsemen and his army, overtook them …» 14:21+ « … And Moses stretched out his hand over the sea, ant Yahweh caused the sea to go back by a strong east wind … and the waters were divided … and the waters were a wall for them on both sides … and Israel saw the Egyptians dead on the sea shore … And the people feared and believed Yahweh, and his servant Moses.»